The Next Silicon Valley

Monday, August 9, 2010 at 01:47AM

Monday, August 9, 2010 at 01:47AM In this post, guest Russell Jurney and I explore a historical perspective of the widespread efforts to reproduce Silicon Valley in cities across the world

What is Silicon Valley?

An economic cluster. A network of networks, rich in financial and social capital spanning every area of technology, all focused on developing and commercializing new technologies.

It is the center of a one hundred ten year technological renaissance, the Florence of our time. The most determined, hungriest, and most talented have flocked to the Valley from every corner of the world for more than a century to build thousands of companies that pioneered many of the technologies that underpin global civilization.

From the office of every executive and government official in America and across the world, the Silicon Valley booms inspire envy, curiosity, and attempts at emulation. The busts draw ridicule and cynicism.

The Valley has now extended throughout the Bay Area. The furvor of innovation has infected the peninsula from San Francisco to San Jose. Many cities and regions outside the Bay Area have attempted to reproduce Silicon Valley. Despite their efforts - the Silicon Valley ecosystem has remained highly localized. That physical location would come to matter more than ever in a densely networked global economy is counter-intuitive, but economic clusters have come to dominate every area of technology.

Despite the Bay Area's dominance, new micro-clusters sprout and grow across the globe. As each new seed develops, the comparison is inevitably made: is this the next Silicon Valley?

Can VCs replicate the valley in Europe?

Is China the next silicon valley?

Is New York the Next Silicon Valley?

Thoughts on Creating a Russian Silicon Valley

Georgia Tech as the basis to try to develop a Silicon Valley

Along with these questions comes the occasional, is the valley losing its edge?

What would the 'next Silicon Valley' look like and what does the comparison really mean?

Arisen from a Vacuum: The Corner of and Emerson and Channing

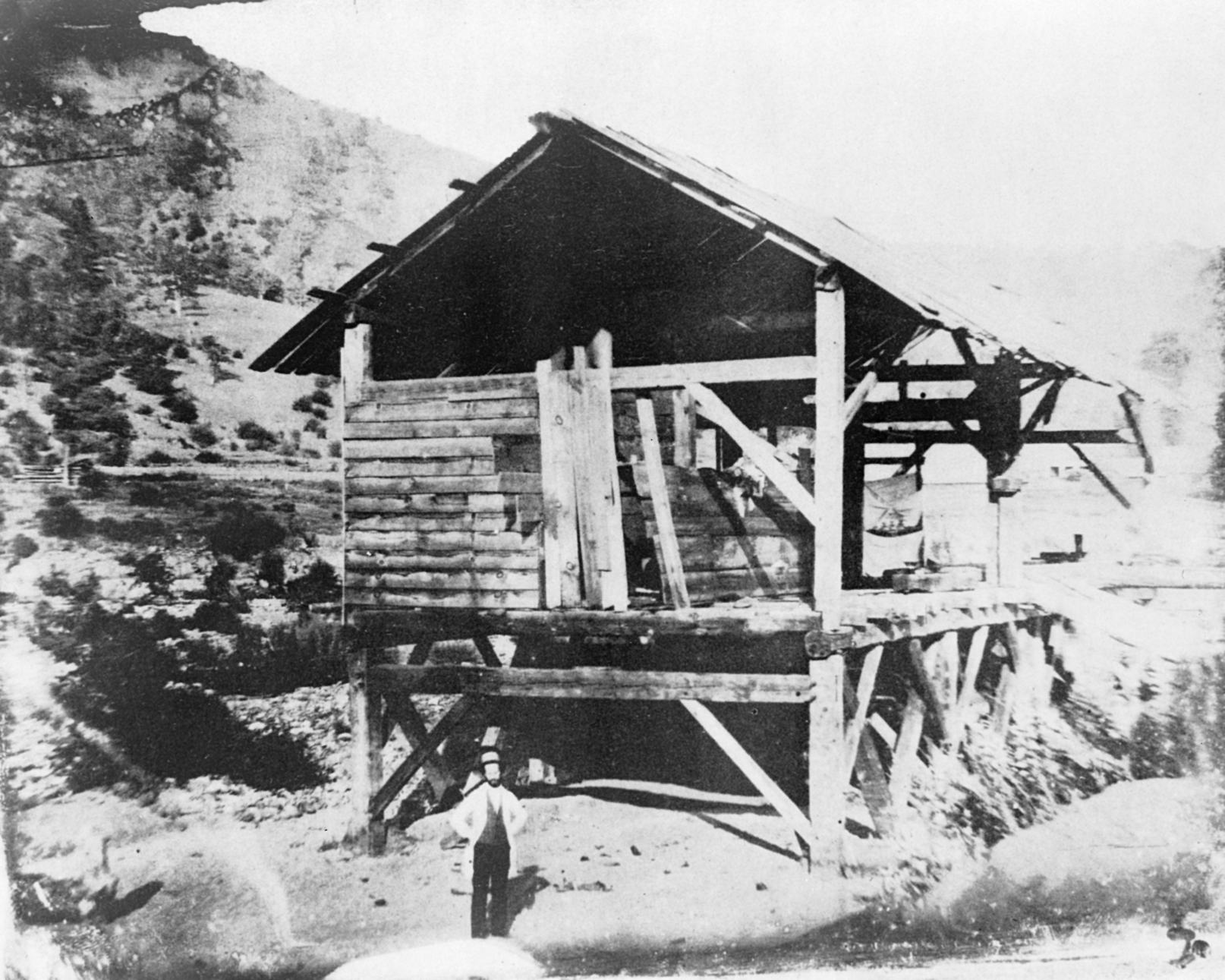

Silicon Valley's rich ecosystem is over a century in the making. To understand where the valley is today, let's start ninety nine years ago at the corner of Emerson and Channing in downtown Palo Alto.

It was here that Lee De Forest, the Father of Electronics, developed the triode amplifier at Federal Telegraph between 1911 and 1913. The triode amplifier goes by another name: Vacuum Tube. Vacuum tubes made cheap, powerful radios possible and went on to be the basis for television, radar, and electronic computers.

It was here that Lee De Forest, the Father of Electronics, developed the triode amplifier at Federal Telegraph between 1911 and 1913. The triode amplifier goes by another name: Vacuum Tube. Vacuum tubes made cheap, powerful radios possible and went on to be the basis for television, radar, and electronic computers.

De Forest happened to be in San Francisco in 1910 installing radio transmitters on US Navy ships when his company back in New York collapsed. De Forest got a job at Federal Telegraph in Palo Alto, and the Bay Area developed an early lead in radio technology in the early twentieth century. Radio technology snowballed into radar, television, electronics, computers and eventually modern software, and the internet.

That Federal Telegraph was able to recruit such a pivotal figure in the history of technology was more than historical luck. As we shall see, forces were already in place that enabled such serendipity.

The Radio Bay

San Francisco had a lot going for it at the turn of the 20th century. It was an energetic, adventurous town still characterized by the pioneer spirit of the California Gold Rush of 1849. San Francisco's population boomed from 35,000 in 1850 to more than 400,000 by 1911 - nearly half its present population. A Phoenix city arisen from the rubble of the 1906 earthquake, in San Francisco anything was possible.

San Francisco grew into a metropolis around of the Port of San Francisco, a port in which "in which all the fleets of the world could find anchorage." Established in 1853, the Mare Island Naval Shipyard was the first naval shipyard on the pacific coast. It was joined in 1870 by the San Francisco Naval Shipyard, which became the largest dry dock in the world by 1916.

Ship-to-shore communication was a pressing problem effecting the bay area's economy. The US Army Signal Corps were stationed at the Presidio, and employed carrier pigeons and a limited cable telegraph network at the turn of the century. There was also a pressing need to contact Pearl Harbor in Honolulu.

The descendants of gold miners and pioneers, Californians were always early adopters and innovators. California led the nation in adopting agricultural mechanization, and it was in San Francisco that the first ship-to-shore radio transmission in North America took place at the Cliff House on August 23, 1899. This was one month before Nobel prize winner Guglielmo Marconi, who started the first telegraph network, arrived in New York from Europe.

Radio companies began appearing in San Francisco soon after that first transmission, and they sound much like the social networks of today: risky investment in new mediums of communication. One such company was funded by a public offering of stock by its founder, a 10 year old boy. A culture of collaboration among radio 'hams' developed. That same culture characterizes the valley today: intensely competitive and collaborative.

Radio spread through the Bay Area like wildfire. The first full-time radio station with regular programming was in San Jose, and by the 1920s the Bay Area had more operating radio stations than any other city in the world. The technology economy of the early Bay Area was still tiny until mid-century, but the foundations of the valley were built during this time.

Radio startups employed hams - self-trained amateurs. Radio geeks, pragmatic experimentalists without formal educations in physics and math. These men were radio hackers, who cared most of all about advancing the applied science of radio and helped one another to do so - across company lines.

Much of present day startup culture is the culture of California and San Francisco that was already present at this time in the companies that sprouted around Federal Telegraph and Stanford. The culture was in place, but as radio became increasingly technical, institutional support was needed to drive research and train engineers. That help came from Leland Stanford.

The Rise of Stanford

Leland Stanford was an attorney in Wisconsin when his office went up in flames in March, 1852. Stanford and his wife Jane Elizabeth Stanford went west, following his five brothers to California where he joined them in operating a general store. It is often said that the men who really got rich from America's gold rushes were the operators of hardware stores. So it was with the Stanford brothers: their general store grew into a supply depot, and then into a fortune. Stanford became a full-blown tycoon - California Governor, US Senator, Grand Master Mason - his interests came to include Wells Fargo, Union Pacific, and the Occidental and Oriental Steamship Company.

The tragic death of their only son, Leland Stanford Jr., left the Stanfords without an heir to their fortune. They decided to 'adopt the children of California' by founding Leland Stanford Junior University, on the site of their 650 acre farm just outside Palo Alto. Progressive from its inception in 1891 - Stanford was both coeducational and tuition free. Science at stanford placed an emphasis on applied research: original research directly applied to enhance the lives of the people of California. At Stanford, this idealism of applying research in new ways has always been the norm. This view of research would develop into what is the most successful university-industry collaboration in history.

The Startup Cycle Begins

It was Stanford's enlightened culture which enabled the employment of De Forest in Palo Alto. Founded in 1910 by Stanford student Cyril Frank Elwell, the company that would become Federal Telegraph was the first American licensee of Valdemar Poulsen's arc wireless transmission method. Federal Telegraph operated one of the first major telegraph stations in the United States at Ocean Beach.

Federal Telegraph was the source of the first Silicon Valley founder diaspora, including two employees who went on to invent the loudspeaker and found Magnavox.

Radio's importance during the first world war grew the market dramatically, and radio stations appeared nationwide. RCA came to dominate the industry back east, strangling any competition with patent gangsterism. As a result, valley firms had trouble competing in the broader market. Isolated from RCA's east-coast attorneys on the west coast, they found their niche in selling high performance equipment to radio amateurs - a market they understood very well, as they were a part of it.

Cultural Innovation

As radical then as it is today, San Francisco was one of the strongest union towns in the United States. The labor party controlled the city government in 1910. Unionization posed a problem for Bay Area radio component manufacturers. Manufacturing high precision vacuum tubes for amateurs in a tight-knit community that would accept nothing less than the best quality was difficult and demanding work, requiring strict standards and continuous innovation. Shops competed by achieving incremental improvements over previous designs and other shops. This involved applied electromagnetic research - physics and materials science, as well as high precision manufacturing - much of it by hand. In order to survive, companies needed to be able to fire bad employees and retain and develop only the most talented - in the lab and on the line.

Had these factories unionized like much of the Bay Area's industry, they would have been driven quickly out of business. They responded by innovating. Applying labor reforms pioneered by FordEastman Kodak, management started treating their employees in much the same way that startups treat their employees today: as equals. Ham radio egalitarianism persisted, and enabled them to keep their workers too happy to unionize. Healthcare, free or subsidized lunches, communal decision making, profit sharing. Startup culture, much as we know it today was present right from Federal Telegraph onwards, nearly one hundred years ago. It arose as a combination of the culture and factors of the bay area, the bonds of a tightly knit sub-culture, and with the support of Stanford it began to scale: the valley's protean economy prospered.

Startup DNA as we know it today was already present by 1920. From Federal Telegraph, to the Traitorous Eight and the Fairchildren, to the Paypal Mafia of today - it is this egalitarian culture, that is simultaneously collaborative and intensely competitive and is rich in social capital that produces the wealth of the Valley. Networks of companies supplying one another, collaborating and competing. Each successful company breaks new ground and trains and supports new founders that spawn new companies that continue to blaze a trail in new markets as technology develops and changes. The culture predates the ecosystem. The ecosystem grew from the culture.

Fred Terman Turns up the Volume

Frederick Terman joined Stanford's engineering staff in 1924 and set out to build a world-class electronics program. Terman took Stanford's focus on applied research to the next level. He aggressively integrated Stanford's electronics labs with local industry, going as far as to send academic 'agents' to local companies to learn their techniques and reproduce them in Stanford's labs. He encouraged students to commercialize their research, including Bill Hewlett and Dave Packard.

Following a post at the Radio Research Laboratory at Harvard during the second world war, Terman pursued policies to increase Stanford's military research and development budget.

The war had another effect: it enabled bay area radio companies to break out of the hobbyist market into larger markets through military contracts. High quality radio components were critical to naval convoys, and so RCA was unable to use its clout to muscle out smaller companies out west. With lives on the line, quality was king, and components from the bay area were superior to any others available at that time. They got the contracts, and the industry grew.

The genius of Terman was not to cast a vision of the future drawn purely from his imagination, or to imitate the east coast, but to recognize the potential of what was already there. He nurtured the valley economy - while it was still miniscule - into the powerhouse it had become by his retirement in 1965. Terman interned at Federal Telegraph - he knew the potential of these companies first-hand, so he worked tirelessly to connect them to Stanford and to the federal government.

This is where we enter the 'Secret History of Silicon Valley.' Billions of dollars of federal money entered the local economy through federal research and military contracts. The protean startup ecosystem was amplified, and it grew to new industries pioneered through basic research: first power tubes for the electrical grid, then test equipment, microwave and silicon.

Economic Clusters

Cultural and geographic forces led to the Bay Area's early lead in radio technology, and the radio economy grew into industries based on radio technology and then beyond. It did not arrive at them by coincidence or by central planning. Silicon Valley had an early lead, and was nurtured, not directed, into what it wanted to become.

No other region was so primed to achieve this snow-ball effect because no other region's factors were so aligned at the birth of the modern era. No one could have looked at San Francisco or Stanford at the dawning of the 20th century and laid out a reasonable plan to arrive at the economy of today.

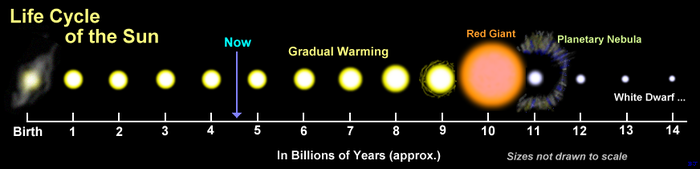

Radio grew into power tubes, power tubes grew into test equipment and mircowave components, test and microwave equipment grew into silicon, silicon grew into computers, computers grew into software and networks, software and networks grew into social networking. A lead in each area enabled the valley to pivot to the next.

Successful startups train founders that enter new markets and industries. Clusters creep into new sectors one startup at a time, paving the way for others to go further. This rapid cycle enables the Bay Area to lead, not follow, across many sectors because it is always pivoting in many directions.

Is Dayton, Ohio the next Silicon Valley?

Dayton, Ohio is an interesting case in the history of innovation.

Dayton had more granted patents per capita than any other U.S. city in 1890 and ranked fifth in the nation as early as 1870.

Dayton was an innovation center for a short period of time, and the home of the Wright Brothers.

Wilbur did not attend Yale as planned. Orville dropped out of high school after his junior year to start a printing business in 1889, having designed and built his own printing press with Wilbur's help...Capitalizing on the national bicycle craze, the brothers opened a repair and sales shop in 1892 (the Wright Cycle Exchange, later the Wright Cycle Company) and began manufacturing their own brand in 1896. They used this endeavor to fund their growing interest in flight.

There were other people working on flying machines, and they had lots of government funding. Many were earlier, had superior formal education, better funding, and better contacts.

But we all know who the Wright Brothers are because they were passionate and worked tirelessly to create working airplanes. The Dayton area has been an innovation hub for aviation to different degrees ever since. It was only after factors aligned to produce excellence in aviation that Wright-Patterson Air Force Base channeled federal money to sustain the cluster.

If you had a modern-day equivalent of the Wright Brothers in your city, would you recognize them, or are you to busy figuring out how to duplicate the valley?

A Culture of Innovation

In silicon valley, entrepreneurship is a profession and startups are an industry. This is part of a culture of both bold and calculated risk taking, alongside an acceptance of failure. The valley culture is the one factor that trumps all others.

Creating a center of innovation requires creating a culture of innovation.

Some folks in NYC understand the value of this culture.

California should be NYC’s role model and ally. The enemy should be people and institutions who make money but don’t actually create anything useful. In NYC, this mostly means Wall Street, along with the Wall Street mindset that sometimes infects East Coast VC’s (emphasis on financial engineering, needing to see metrics & “traction” vs betting on people and ideas, etc).

The capital and talent network, combined with the culture of calculated risk taking and acceptance of failure is a potent combination that is extraordinarily difficult to emulate.

There is No Such Thing as the Next Silicon Valley

Efforts to duplicate silicon valley tend to fail because they attempt to follow the valley by looking at where it is now. They don't look at the century of history.

It is easy to look at a single pivot and formulate policy without considering context. Without considering a long-term view. To focus on the icons of our age: Steve Jobs, Mark Zuckerberg. To enact policy that encourages collaborative cultures and to bootstrap a funding ecosystem with federal and state funding.

Yet, those circumstances that made the Valley possible are actually difficult or impossible to achieve elsewhere because they require fundamental changes to regional culture. The culture of the Bay Area arose as a response to its unique situation by the diverse peoples that make up its population. A plan bent on reproducing Silicon Valley starting at the gold rush of 1849 would be more rational than a plan that attempts to leapfrog into the 1980s. Dramatic cultural change without an overwhelming catalyst or crisis is not something that happens in the span of a business cycle, it is something that happens in the course of one or more human lifetimes.

These efforts fail because they try to duplicate the valley rather than reflecting on their own circumstances and finding how to create a center of innovation in their own way, amplifying their own unique potentials into their own unique better tomorrow. They see one boom and emulate it. They see the short term. They do not see the past. They do not see the context, or the trajectory. They are Heisenberging the valley at some snapshot in time.

Toward A Local Vision

Attempting to replicate the valley means attempting the replicate all of its unique circumstances: its 100 year cultural legacy, its existing network of clusters, its financial ecosystem and network of service providers, and its strong research university with a focus on application. You cannot simply jump to the present. Nor can you simply mix the Valley's ingredients in your city and expect similar results.

You can draw a similar path for Route 128 and Boston having arisen from the Lincoln Project for Nuclear Defense at MIT having a hard real-time requirement for computers, and research leading to the minicomputer and the birth of that startup ecosystem. Although note - it hasn't fared as well, lacking some of the cultural ingredients that makes the valley work so well.

Some people think that the capital infrastructure in the valley is the key - but remember that in the beginning there was no venture capital, and the early valley prospered without it. Stanford professors were the first angels investors. Nevertheless, we now enjoy the deepest and most savvy startup investment network in the world, which has become extraordinarily difficult to emulate. New York City, with a truly massive investment network, has only a tiny fraction of that network with the requisite savvy to back technology startups intelligently.

A better plan than imitation is to reflect on what you are passionate about, what you can do now with your own location, what the advantages and disadvantages are, and start innovating in your own way. What can your city be world class at? As Steve Blank says, no successful startup ecosystem was built from local talent. How can you draw the best talent from all over the world? The valley draws talent from all over the world. It hasn't been dependent upon local talent since De Forest showed up at Federal Telegraph. What can you do to attract world-class talent to a cluster you already have?

Can you create a center of innovation now in a totally different way? Perhaps cheaper and in less time? Perhaps new commodity technologies (broadband internet, cloud computing) and new industries (data mining) would allow something similar to occur without any initial government or university funding?

Effective stimulus of regional clusters requires that you identify and monitor the clusters you have. To spend limited resources effectively, you must early detect shifts as clusters pivot and grow, one startup at a time, to guide your research university and spend incentives effectively. Actively engage leaders in your cluster, find out where talent and capital are headed and then support those new directions. For example, a watchful eye could have detected the emergence of Atlanta's security cluster from its broader enterprise software and finance and payments clusters and directed stimulus at this area.

What factors are working in your city's favor in a particular area more than any other city in the world? The way to create the next silicon valley is to not try to create the next silicon valley, but to reflect on your city's passions, circumstances, personality and resources, and then innovate accordingly.

--------

Image On Click Links:

Stanford Family http://www.stanford.edu/about/history/

Audion http://www.leedeforest.org/inventor.html

Open to Experience People http://creativeclass.com/whos_your_city/maps/#Personality_Maps

Population of San Francisco http://www.wolframalpha.com/input/?i=population+of+san+francisco

Lunch at Twitter (needs caption) http://www.flickr.com/photos/twitteroffice/3344991684/

Radio Economy Employment Growth: http://books.google.com/books?id=VRz9LfC85pYC&lpg=PP1&dq=making%20silicon%20valley&pg=PA6#v=onepage&q&f=false

Fairchildren poster - link to the full res version some place, have to post/host it

Bibliography

Electronics in the West: The First Fifty Years, Jane Morgan, 1967

Regional Advantage: Culture and Competition in Silicon Valley and Route 128, Annalee Saxenian, 1994

Making Silicon Valley: Innovation and the Growth of High Tech, 1930-1970, Christophe Lecuyer, 2006

The Secret History of Silicon Valley Rev 4, Steve Blank, 2009

The Secret History of Silicon Valley, Presentation at Computer History Museum , Steve Blank, 2008

Steve Blank's Blog, Secret History Posts, www.steveblank.com, 2008, 2009

Lee de Forest: Advancing the Electronic Age, Donald Wollheim, 1962

Father of Radio: The Autobiography of Lee de Forest, Lee de Forest, 1950

San Francisco: Mission to Metropolis, Oscar Lewis, 1980

The Competitive Advantage of Nations, Michael Porter, 1998

A History of Modern Computing, Paul E. Ceruzzi, 2003

The Making of Silicon Valley: A 100 Year Renaissance, Ward Winslow, 1995

Outliers: The Story of Success, Malcolm Gladwell, 2009

Computing in the Middle Ages: A View From the Trenches 1955-1983, Severo M. Ornstein, 2002

The Dream Machine: J.C.R. Licklider and the Revolution that Made Computing Personal, M. Mitchell Waldrop, 2002

Who's Your City?: How the Creative Economy is Making Where you Live the Most Important Decision of your Life, Richard Florida, 2008

Geek Silicon Valley: The Inside Guide to Palo Alto, Stanford, Menlo Park, Mountain View, Santa Clara, Sunnyvale, San Jose, San Francisco, Ashlee Vance, 2007

The Origins of the Electronics Industry on the Pacific Coast, Arthur L. Norberg, 1976

No comments:

Post a Comment